After the trailers ended and the lights went down, the first image that greeted the moviegoers who caught Stalker in 1979 was the logo of the USSR’s Mosfilm studio., which shows the famous socialist realist statue Worker and Kolkhoz Woman. Sculptor Vera Mukhina intended the two figures, who reach towards the sky and the future bearing hammer and sickle, to inspire pride in the present and hope for the future, and perhaps they are beautiful when viewed without context, but it’s hard not read them as icons of totalitarian kitsch and state-enforced taste. Andrei Tarkovsky’s film, however, provides none of the comforts of kitsch or the assurances of dogma.

Stalker was the first adaptation of Boris and Arkady Strugatsky’s influential novel Roadside Picnic, one of the very few Soviet science fiction novels to make it over to the West during the Cold War. Both film and novel tell the story of the Zone, the barred and blockaded site of a mysterious alien visitation, a once-inhabited area as inscrutable and dangerous as it is alluring. Barbed wire and machine guns guard the Zone, yet still treasure seekers, true believers, and obsessives continue to seek entry. Nature thrives in the Zone, but nothing human can live there for long. There are no monsters, no ghosts, no eruptions of blood and horror, but the land itself has become hostile. The ruined tanks, collapsing buildings, and desiccated corpses that litter the Zone should be ample warning, but they are not.

There’s a temptation, when writing about an adaptation, to make a point-by-point comparison between the original work and the story’s new form. I won’t do that here, but I should talk about the contrasting effects the two versions of this story had on me. Roadside Picnic, much as I enjoyed it, felt ephemeral: I remember the final scene and a little bit of the opening, yet my strongest memories of the book come from the forewords and reviews—all of them praising the book and assigning it a central place in the science fiction canon—that I’d read beforehand. Stalker, by contrast, might best be described as indelible—however nebulous its meaning and however cryptic its story, Stalker is the rare film that will stay with sympathetic viewers for their lifetimes; and so for the remainder of this piece I will discuss the film alone.

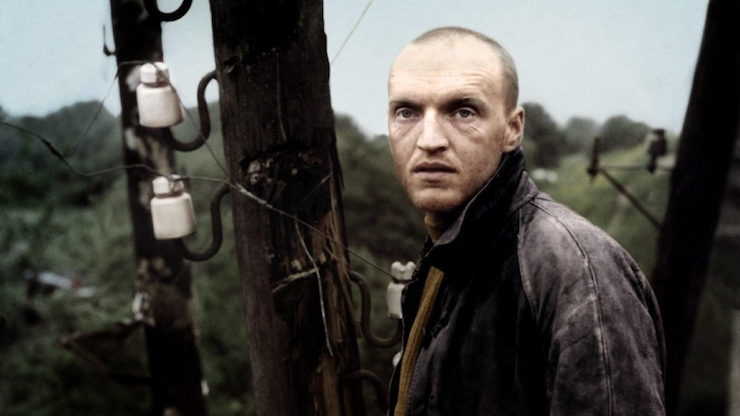

There are just five credited actors in Stalker, and none of the characters receives a proper name. There is the Stalker, recently returned from prison, where he was sent for the crime of entering the Zone. Despite the years lost to his crime, he is desperate to reenter the Zone. There is the Professor, whose stated desire for knowledge may be a pretext for less lofty motives. And there is the Writer, successful yet cynical, whose fluency belies his purported lack of inspiration. Finally, there are the wife and the sickly daughter (nicknamed “Monkey”) that Stalker abandons as he guides the Writer and the Professor Zoneward. It’s said that there is a Room (always capitalized) at the center of the Zone that will, for unknown reasons and through unknown means, grant the deepest wishes of anyone who enters.

Stalker’s first scenes take place in grubby sepia in a dirty town outside the Zone. Had Tarkovsky shot in black and white, the unnamed town would seem sad and sparse, but the oppressive sepia tint over everything renders this dingy world almost overbearingly oppressive. It is so sickly looking that military police who guard the Zone—and shoot to kill any trespassers they spot—hardly make the world bleaker. (The guards do, however, make a political reading of the film much easier for those inclined to make it.) Our three travelers evade the guards; their entry into the forbidden territory is marked by the sudden appearance of color. We are overcome and relieved, yet also wary: What new world have these pilgrims entered?

As Geoff Dyer, author of a book on Stalker, says in an interview included on the new Criterion Blu-Ray, one of the film’s most remarkable qualities is its resistance to interpretation. Archetypal characters reveal themselves as unique individuals; established facts waver and evaporate; desperately sought goals become objects of dread. Stalker, Zone, Room—none escapes ambiguity or interrogation. We may well leave the film knowing less than we did when we entered.

Stalker is a slow and meditative film; Dyer points out that despite a runtime of 161 minutes, it’s composed of just 142 individual shots; the average shot length is over a minute. These long shots are not the showy and self-conscious exercises in style of contemporary movies like The Revenant or Children of Men; they’re frequently static, and camera movements are measured, even tentative. Tarkovsky’s second feature, Andrei Rublev, was a biography of a Russian ikon painter, and at times Stalker acquires the character of an ikon. We contemplate more than watch; as the camera lingers over the abundantly decayed textures of the Zone and the watchful and uncertain faces of its explorers, we’re afforded a rare opportunity to see the world anew.

Still, for all his love of long takes, controlled shots, and deliberate pacing, Tarkovsky was also a believer in flashes of insight and the promise of improvisation. Tarkovsky rewrote Stalker’s script on set after early footage was destroyed; he scrapped his plan to shoot the Zone in a desert and plopped it into a verdant corner of Estonia; he was a meticulous framer of tableaux who made a hobby of his relish for the “instant light” and immediate results of Polaroid photography. Perhaps this is why, for all its distancing camera setups, unnamed characters, unexplained phenomena, indistinct geography, and inconclusive conclusions, Stalker never seems like a cold film.

I may have made Stalker sound dreary, mannered, and boring, and I have no doubts that many viewers will abandon the movie well before the Stalker reaches the Zone and the sepia evaporates into color. It offers none of the pleasures of a blockbuster, but it is one of the very few films to successfully convey (or evoke) the uncanny, the unknowable, and the fundamental mysteriousness of existence. Like the Zone itself, Stalker rewards patience, attention, and flexibility. Enter in the right spirit, and perhaps some of your wishes will be granted.

Stalker is now available on Criterion DVD and Blu-Ray in a new restoration. As of this writing, the restoration continues to show in some repertory theaters.

Matt Keeley reads too much and watches too many movies; he is helped in the former by his day job in the publishing industry. You can find him on Twitter at @mattkeeley.

What an odd coincidence – just last night I was listening to the DVD commentary for the Doctor Who episode “Terminus” (1983) and the writer mentioned that his script (about a ship full of lepers on a doomed journey) was influenced by this film, which I’d never heard of before!